EVs could make dealerships a thing of the past, too

There’s auto news out of Sweden: Volvo Cars says that it will be fully electric by 2030. No more internal combustion, no more hybrids. It’s batteries or bust.

In making this commitment, Volvo is betting on a trend: that as EVs are becoming cheaper and new conventional cars are being priced higher, consumers’ math on electric-versus-internal combustion will soon come out in electrics’ favor.

But there’s more to Volvo’s position on EVs than just changing the powertrain. The carmaker says its pure electric models will only be available for sale online, and that its first fully electric car is now receiving over-the-air software updates. (Tesla has been doing this for years.) That first plan has implications for the built environment; the second, for emissions and the global climate.

I’ve talked before about what increasing electrification means for the gas station, an icon of the American landscape. There are more than 100,000 of them, they employ more than 900,000 people, and not all of them will survive a world with many more electric vehicles. We can apply that same lens to the auto dealer landscape — and when we do, the numbers are even bigger.

There are almost 118,000 car and parts dealers in the U.S. — fewer now than before the global financial crisis, but more than the low in 2011.

Those dealerships employ nearly 2 million people — more than twice as many as filling stations employ — after a dramatic drop-and-recovery in 2020. Prior to Covid-19, that number was at an all-time high after rising for nearly a decade.

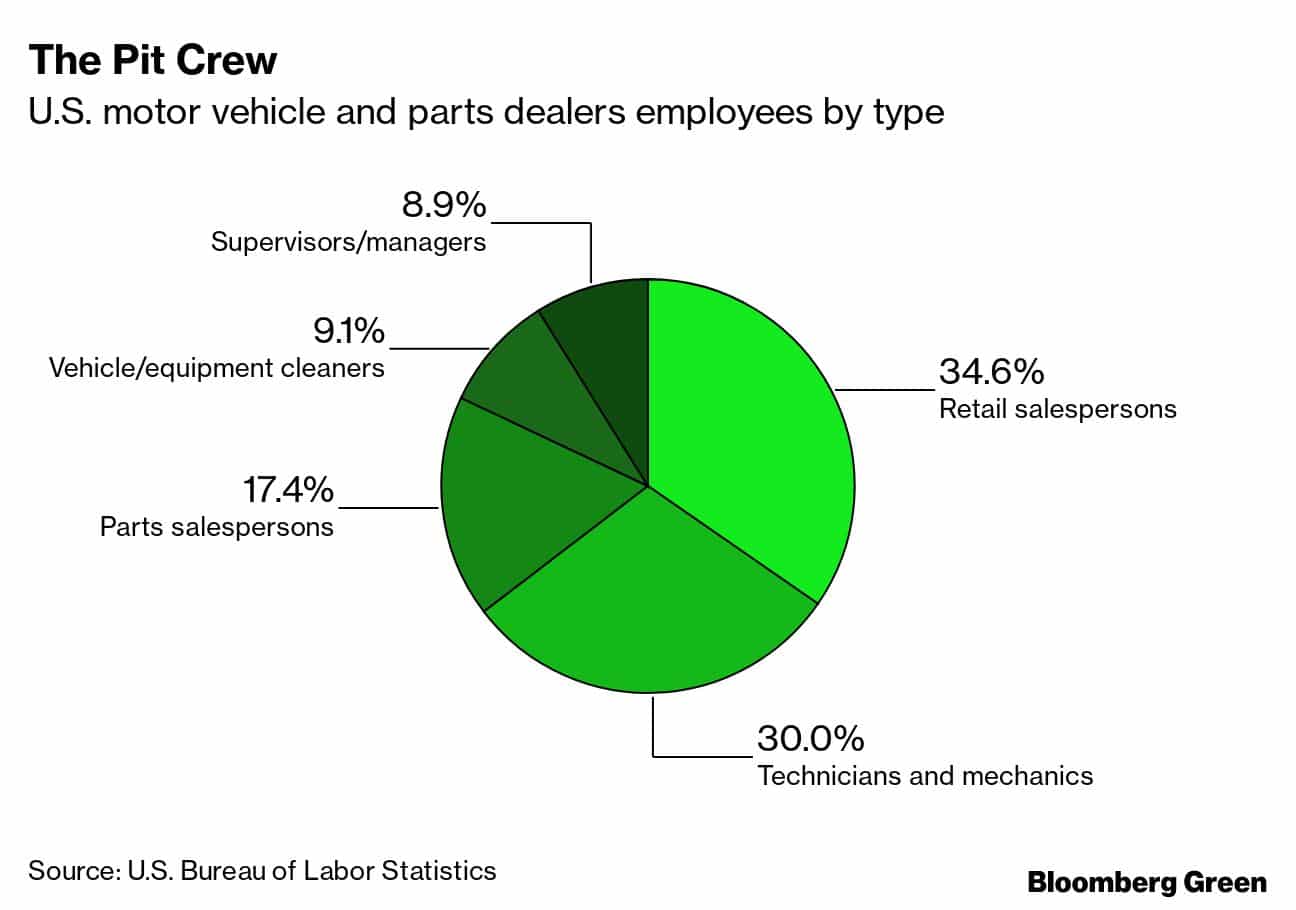

More than half of those employees work in sales, and another 30% are technicians and mechanics. That’s a different distribution than gas stations, where almost everyone works as a clerk or prepares food, and it also gives an indication of what’s at stake for dealers with electrification.

Volvo says that its retail partners will still take part in “selling, preparing, delivering, and servicing cars,” but that it “will radically simplify the process for, and reduce the number of steps involved in, signing up for an electric Volvo.” Just about anyone reading that would bet that means fewer people involved, too.

A digital sales channel changes not only the number of people needed to sell a car, but also the nature of their jobs and where they work. It means no one waiting in a showroom for people to drop in, no office managers, no janitors. EVs also have far fewer moving parts than internal combustion engine vehicles, and therefore are far less likely to need the same level of service. That’s part of the logic behind a Michigan bill that would have banned privately held electric vehicle companies from selling directly to consumers. (The bill died quietly at the end of last year.)

And then there are the updates. Modern cars contain dozens of software-embedded electronic-control units, i.e. the sort of things that could be updated over-the-air. Cars that can be remotely updated aren’t driving pointless miles to fix something that actually prevents them from being safely driven. That could also help cut down on costly recalls — last year, Toyota recalled 2.9 million cars in January for an issue with one of its electronic-control units.

But perhaps more important than avoiding millions of miles of driving for recalls — and therefore millions of miles worth of unnecessary emissions — is the promise of vehicles that improve over time. Here again, Tesla is setting the standard, doing not just over-the-air updates but also upgrades. These aren’t just patches or fixes; they’re permanent enhancements, which will keep cars on the road longer with — you guessed it — less maintenance. That’s another blow to dealers, but a boon to consumers, and to the climate.

– By Nathaniel Bullard